Accueil |

Articles |

Photos |

Profil |

Contact |

Joys And Pains Of Reporting India

Thèmes: Société |

Outlook, 30 décembre 2015

For a foreign correspondent, India is something like Heavens on Earth. No kidding.

Cet article a été écrit pour l’hebdomadaire Outlook qui préparait un ensemble sur les journalistes étrangers en Inde. Le projet d’ensemble a été abandonné mais le magazine a mis mon article en ligne sur son site. Note pour les lecteurs français peu familiers de l’Inde: North Block désigne l’un des complexes de bâtiments accueillant la tentaculaire administration du gouvernement indien, le “PAN number” est le numéro d’identification attribué aux contribuables, qu’il s’agisse d’entreprises ou de particuliers.

Patrick de Jacquelot

For one thing, you never have to worry about finding stories to write about: every single morning, you run into incredible events ("One gas bottle explodes, one hundred dead" — "so sad", they say at the head office, "but it makes for such a good headline"), totally unexpected news ("Sale of meat banned in Mumbai") and out of this world scandals (list too long to take one example).

For one thing, you never have to worry about finding stories to write about: every single morning, you run into incredible events ("One gas bottle explodes, one hundred dead" — "so sad", they say at the head office, "but it makes for such a good headline"), totally unexpected news ("Sale of meat banned in Mumbai") and out of this world scandals (list too long to take one example).

Accordingly, you find yourself writing colourful stories, both informative and entertaining, which they love in Paris. Then, you get to visit outstanding and exotic places such as Ladakh or North Block. And you meet fascinating people, from NGO workers dedicating their lives to the fight against poverty, to IAS bureaucrats so skilled they can deal one day with coal mining in Jharkhand and the next with the promotion of traditional miniature painting in Rajasthan.

So, for somebody like me who spent seven years in Delhi as a correspondent for the French business daily Les Echos, this was a terrific assignment. Of course, to "sell" those typical Indian stories to a European editor, the foreign correspondent needs to hone his pedagogic skills: "Yes, it may sound incredible but the Union Carbide factory in Bhopal is still exactly as it was the day after the disaster thirty years ago!"; "I know you don't believe me but the Government of India made it its business to decide Ikea must not have a restaurant in their shops". Even very basic things need a lot of explaining, like when I was told that a French bank was launching a new activity "in a completely unknown town called Mumbai — why didn't they go to Bombay like everybody else?"

On top of pedagogy, writing about India teaches you patience. After two or three years, I realised I was now in possession of some stories with a very distant sell-by date, which I could reuse again and again with minor modifications, such as the one about the imminent resumption of the Free Trade Agreement negotiations between India and the European Union. I was able to print three times a year my bestseller, about the opening of the insurance sector to FDI being on the schedule of the new session of Parliament (unfortunately, that one died last March when Parliament actually adopted the reform).

These new skills of patience I had to share more than once with my colleagues in Paris: "yes India has agreed to buy 126 Rafale fighter jets but it doesn't mean it will happen quickly"; "well, yes, they are now committed to buying 36 planes, but it might take some time, you never know".

|

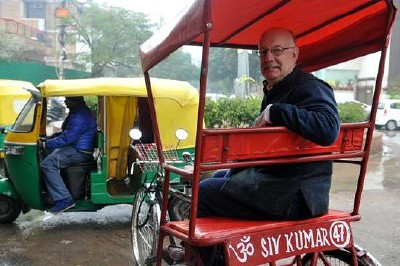

Photo Tribhuvan Tiwari, Outlook |

Another pleasure of writing about India is, of course, the incredible range of topics from demonstrations against rape to the logistics sector. A variety which could seem intimidating at first glance but the seasoned journalist knows better than to worry too much about subjects he doesn't know anything about: first, they know even less than you about it back there at home, and then, as the saying goes, "in India everything is true and its opposite too", so you can never be entirely wrong, can you?

Now, there is a price to pay for being in a foreign correspondent's paradise, of course. One specific difficulty, when you write for a French business daily nobody has ever heard about in India is that, well, people might just not be immensely interested. For several years, I tried to be put on the mailing lists of several big ministries such as Finance, Commerce & Industry and the like. On calling the prescribed number I would be told to call another one to which usually nobody attended. When finally I got to talk to somebody in charge, I was told to send an email detailing my request, to which I never got any answer. And so on, and so on.

With politicians, it was very much the same story. On occasions too numerous to be counted, I ran into ministers during big conferences in these Delhi five-stars. This 35 seconds dialogue would ensue: "Minister-I-am-the-correspondent-of-the-French-business-daily-the-equivalent-of-the-Financial-Times-in-Britain-(a clever way of showing the importance of my unknown newspaper — although it didn't work)-could-we-do-an-interview-please?" The minister: "of course, terrific, we must do that, give your card to my assistant", (to the assistant) "make sure we meet next week". Endless phone calls and emails later, it appeared that the Hon'ble minister would never find the time. And not surprisingly, the attitude of the top-level bureaucrats mirrors precisely their masters'.

During all my years in Delhi, the only exception was a minister whose previous jobs included high responsibilities at the UN: very inclined to international contacts, he was always ready to talk. I realised later that he was in fact somewhat too ready to talk and this landed him regularly into trouble.

So what do you do in India when you can't go through the normal way? You use your network of acquaintances. I got my big break when a common friend got me an appointment with the Communications Adviser to the Prime Minister (not the one with the colourful kurtas, the one with a monochrome turban). Wonderful meeting: nice cup of tea at the PMO, a charming interlocutor who took note of all my wishes, drew a list of ministers he would ask personally to grant me an interview, and so on. Unfortunately, it seems this went as far as whatever favour he owed to our friend: strictly nothing happened. I must say I sort of gave up after that.

To be fair, the lack of interest towards foreign newspapers is not typical of Indian politicians only. When I was correspondent in London years ago, there was some element of that too. Politicians all over the world are fascinated by the medias with one caveat: they must be read or watched by their electorate.

As can be expected, the correspondent of a foreign business daily gets a better welcome among the business community — just. Among the big Indian companies, only a handful is truly open to contacts with the foreign press: those with a deep international presence, such as the big Information Technology groups or a conglomerate such as Tata. Even then, some surprises can occur, and pedagogy is needed again. I was in the habit of sending a pdf of my stories to anybody I had interviewed, just to show my newspaper was for real. This gave rise on several occasions to the following dialogue.

"Hello, I got your article, thanks. There is a problem, however, it's in French.

- Well, yes of course.

- But we can't read it, send us the English version.

- There is no English version.

- What do you mean, there is no English version???

- I'm afraid, being a French journalist writing for a French newspaper written in French for French readers, there is only a French version…

- You're not serious!"

Another issue which comes back regularly to haunt the foreign correspondent is the question of the visa. The yearly renewal could be a boring routine but thanks to the inventiveness of the bureaucracy, there is always an element of surprise. Last year for instance, after providing the usual number of forms, letters and support documents, I was told: "everything is in order. We just need the PAN number of your newspaper". Taken aback by this strange request which had never been there before, I pointed out to the fact that my paper had no commercial activity in India, no business of any sort, no branch or subsidiary and no staff at all except for me. Accordingly, it could not be expected to pay taxes and have a PAN number. A flurry of coming and going followed this answer and finally, I was asked to give my personal PAN number instead, which I happily did. "OK, it's fine, I was then told. Next year, be sure and bring your newspaper PAN number".

The paperwork involved in getting and renewing a journalist visa makes you wish, at times, you were in Nepal: in that country, there is no notion of a journalist visa. You get a visa on arrival by paying a few tens of dollars, and that's it. True, in other countries it can be worse. To go to Sri Lanka, the help of a PR company advising the government was needed to get a journalist visa. Among the requests was the list of people I was planning to meet. When I politely declined, I was told hurriedly that it was only meant as a way to help me get my interviews, but still…

So, writing in Delhi as a foreign correspondent may have its ups and down but one thing is sure: India is the country where you never get bored.

Accueil |

Articles |

Photos |

Profil |

Contact |